Behind the DALL-E s life-like images there is a complex artificial learning system

The image you see above was drawn especially for this article, but did not require any artistic skills or vein from its author. It was created by DALL-E, an artificial intelligence that can be asked to draw anything. To visually illustrate the point, the author of this article's lack of imagination prompted the author to ask DALL-E to draw 'a robot painting on canvas on a beach during a sunset' and this was one of the countless possible and ever-changing results that artificial intelligence can produce.

DALL-E is one of the most discussed, appreciated and criticised artificial intelligence algorithms, especially since the end of the summer, when a test version of it was made available to everyone, allowing millions of people to experience its capabilities and share its images on social networks, or to illustrate newspaper articles about it. An initial version of this artificial intelligence had been released in January 2021, but with limited capabilities compared to the current one, which surprised many observers and caused concern among illustrators, graphic designers and artists.

The development of DALL-E was carried out by OpenAI, a computer science research lab that is part of the OpenAI LP company, which in turn is controlled by the non-profit Open AI Inc. The organisation had been founded by billionaire Elon Musk in 2015, who had then resigned from its board of directors three years later, while still remaining a donor.

In seven years of activity, OpenAI has developed various tools related to artificial intelligence (AI) systems, focusing mainly on generative models that allow content such as text and original images to be created, as in the case of DALL-E. The very name of this AI comes from the fusion of two words: the name of WALL-E, the robot from the Pixar film, and that of the Spanish artist Salvador Dalí, famous for his surrealist and dadaist works.

Especially thanks to its second version available a few months ago, DALL-E is the best known system for producing images with algorithms, but it is by no means the only one. Several other research groups and developers, as well as companies and various organisations, have realised AI drawing such as Midjourney, Imagen and DreamStudio. Each of these systems employs different algorithms, but with similar operating principles, although in most cases none are able to deliver images as close to the requirements as DALL-E. However, the sector is booming and leads to major improvements with each update, as shown by the very evolution of this technology that has been around for just over five years.

In order to get an idea of how DALL-E and other AIs are able to draw, one has to go back a few years, when the first artificial intelligence systems capable of autonomously describing the content of a digital image began to appear. Developers had submitted large quantities of images available online - and described over time by humans, e.g. by means of captions - using various machine learning systems that enabled AI to learn to see for itself what was contained in an image without captions.

Early models were able to describe the objects in images by providing simple lists. If a photograph showed a bridge with some cars at sunset, the AI returned the following information: bridge, cars, sun. Through the development of other algorithms, the developers were then able to make the AI write captions in natural language, like the one we usually use to communicate. The same caption could then be rendered with greater detail and immediacy: 'cars travelling on a bridge photographed at sunset'.

Building on these advances, between 2015 and 2016 a group of researchers wondered whether it would be possible to follow a reverse process: give an AI the textual description of an image and have it draw it from scratch. They didn't want the AI to do this by retrieving already existing images from Google and putting them together, but for the algorithm to be able to sort of imagine what it was being asked to do textually, translating it into a drawing that never existed before. Smurfs are strange little blue men two apples or so tall, but would the AI have been able to draw yellow ones as tall as two watermelons from scratch?

In a study published in 2016, three researchers from the University of Toronto (Canada) announced that they had succeeded, albeit by having AI create very small images with a definition of 32 by 32 pixels (the screen on which you are reading this article has many thousands more pixels). They asked their algorithm to draw "a very large airliner in flight in a rainy sky" and got what they asked for, although the images were rather stylised and the greatest work of imagination was then required of our brains rather than the AI.

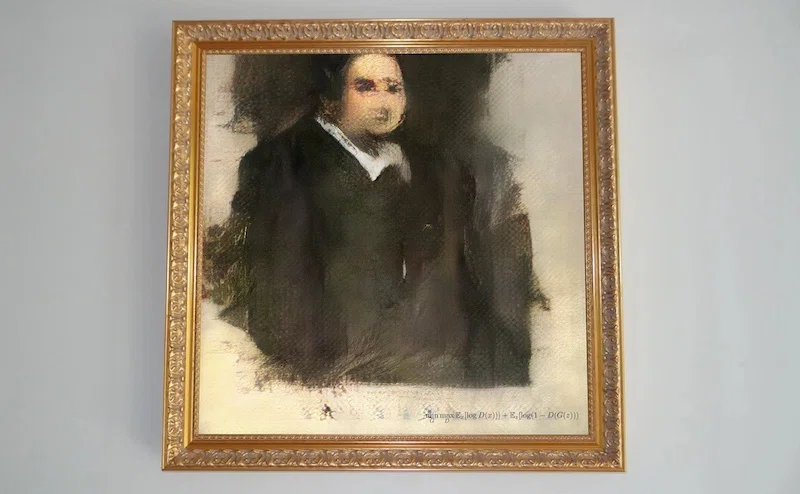

That six-year-old investigation had shown that it was indeed possible to go from text to image via AI, even if the system was still rudimentary. Progress in the field was quite rapid and the non-industry press started talking about it in 2018, when a portrait generated with an evolution of those solutions was sold at auction for $400,000. At that time, AI for drawing was mostly popular among professional computer scientists and computer enthusiasts with the knowledge to calibrate algorithms to achieve specific results. Other drawings, which were still a rarity, were sold at auction for very high prices.

the portrait sold at auction in 2018 for $400,000 (Christie's)

The first systems were quite specialised. If you wanted them to draw portraits, you had to train them for that function by subjecting them to large libraries of portrait images, whereas if you wanted them to draw landscapes, you had to use different, themed libraries. You then needed knowledge of how algorithms work to choose drawing styles and numerous other variables. An AI could be a skilled portrait artist, but a lousy landscape artist. Producing more complex scenes, for instance a portrait of a subject with a landscape in the background and drawn in various styles, was not possible without special computer knowledge and would have taken a few more years of work.

The results of the most recent developments are systems such as DALL-E that are able to draw practically anything, with ever higher levels of adherence to requirements. The latest generation of these AIs is much easier to use than their versions of a few years ago. Just as researchers in Canada had experimented with in 2016, but with much larger and more defined images, it is now possible to write a request in natural language and get the corresponding drawing in a few moments. And you can really ask for anything, such as "a fluffy sloth in an orange knitted hat trying to use a laptop, close up and in great detail, with photo studio lighting and a reflection of the screen in its eyes" (a subject that is getting some success) to get the result you see below.

Thanks to the availability of increasingly powerful computers and libraries containing an endless amount of images with their descriptions, it has been possible to build very rich data sets with which to train AIs that have to learn to draw. Many think that these images end up directly in what is drawn, as a sort of collage of already existing objects: ask for 'a computer sloth', the AI searches for an image of a sloth and one of a computer and puts them together. How it works, however, is different, more fascinating and abstruse for the uninitiated, so we will take some licence to give an idea without using overly complicated words.

An AI does not 'see' images as we see them: it learns things from the numerical values that are assigned to each pixel based on their colour and other characteristics. Since it is dealing with numbers, the AI looks for particular mathematical relationships and on the basis of these metrics arranges what it sees in a mathematical space. It does this by different image features, learning to distinguish objects (it is not naturally aware of what they are, but it can learn to recognise and handle them).

Simplifying a lot, to understand that a certain set of pixels represents the image of a tennis ball or a red pencil, a metric for the AI to consider can be colour: at one end of the mathematical space there is the yellow of the tennis ball and at the other the red of the pencil.

If we add a yellow pencil, things become more complicated, because for the AI, colour is no longer a sufficient metric to distinguish objects, and it therefore needs to insert a new mathematical space referring to shape, for example. Now the AI can relate the two pencils to each other by their elongated shape, distancing them from the tennis ball which is instead round. The latter will still be related to the yellow pencil because of the colour.

Deep learning' algorithms are involved in this process of collecting variables that are then used to create metrics and spaces. As new variables are added, such as the brilliance of objects or unexpected shapes of objects (a broken pencil, a broken and deformed tennis ball or one that is smeared with mud and therefore no longer yellow), mathematical spaces with a large number of dimensions increase. For our brains accustomed to three dimensions, imagining these multidimensional spaces, or rather 'latent patterns', is not easy, but it is from their existence and intricate network of relationships that the AI learns not only to recognise objects, but also to draw them from scratch when asked.

A latent model can have within it hundreds of dimensions that identify particular characteristics of how things are made and appear: the shape pencils have, their colours and the contexts in which they are used, the way they appear in period photographs, the way water reflects them, and a host of other variables, some of which are only 'understandable' to AI and not to us.

Being based on numerical values, latent space has specific coordinates for each point, representing distance or proximity to particular features of objects. A request for a 'fluffy sloth' causes the AI to go back to the co-ordinates of what a sloth is, its distance in mathematical space from fluffy objects, and then to all the other sub-variables, such as its hair, its colour and its characteristics, again in relation to the request.

The coordinates must then be translated from a purely mathematical space to a space that we can also see and interpret, i.e. an image. This intermediate and essential step is a generative process called 'diffusion'. The system starts with a rather confusing set of pixels and through a series of cycles (iterations) gradually puts order into the image, creating one that makes sense to us and responds to the request it receives. In essence, the AI improves the image with each iteration, each time deriving information from the image it has created to make it better. It is a very complex process made possible by systems of encoding and decoding what the AI is doing ('signal') which we will not go into. Again, taking a lot of licence and for the sole purpose of giving an idea, you can think of when you learn to play a song by ear on the guitar, building the melody on the basis of previous attempts gradually improving tempo, rhythm and chords until you arrive at a coherent result, which 'sounds' the way you want it to.

Since there are latent patterns made differently - based on the parameters chosen by the programmers and the images on which the AIs are trained - the resulting images from the queries can vary greatly depending on the final product that is used. Developers can also add further algorithms to sharpen the artistic vein of their AI, for instance by using in the learning phase sets of images that come close to the general aesthetic taste of what we find pleasing or not pleasing to the eye.

Many aspects of how DALL-E works are unknown, but its programmers have indicated that they have added elements to ensure that the images produced meet a certain aesthetic taste. As far as possible, the AI produces images that we should like and consequently that we find more in keeping with our requests, amplifying that impression of having in front of us just what we asked for.

In the image below, produced by asking for a 'squirrel reading a map of Milan', the squirrel appears as we usually imagine these animals: sideways, in a semi-erect position and with its front paws close to its snout. The map does not depict Milan in detail, but it is as we would imagine it: with a tangle of streets, some coloured lines indicating underground routes and green areas for city parks. The image has a fair level of detail, enough to induce our brain to fill in the missing parts. It comes close to our aesthetic taste, or how we would imagine a squirrel grappling with a map, and as a result we attribute to AI an even higher capacity to 'imagine' and produce the image: we project something of ourselves onto its capabilities.

A large number of dimensions means that the AI can also imitate very different styles, which can be included in the request. If, for example, you ask for 'Napoleon in a Soviet poster', you get a consistent result with a good approximation.

The AI shows, however, that it cannot always draw the features of a particular character, and again much depends on the set of images it took to learn to draw.

Those involved in graphic design and illustration in recent months have begun to show a certain concern, sometimes intolerance, towards AIs that draw and do it better and better. One day, perhaps not even too far away, for certain types of illustration the work of professionals could be replaced by AI, something that has not happened in other areas where artificial intelligences have been experimenting for some time, such as in text production, where there is still enormous room for improvement. Progress in drawing with AI has been faster and is above all more promising, hence the many concerns expressed in recent months.

Like all technologies that have only been around for a short time, there are big questions about the implications of DALL-E and its like. To date, there are no copyright rules on AI-generated images, just as it is unclear how the copyright on images that are used to train artificial intelligences to make drawings should be handled. A faithful illustration of Donald Duck made by an AI falls into which category? In that of a reproduction for which royalties have to be paid to Disney, or in a work of art that therefore follows different routes related to copyright? And even if there were royalties to be paid, who would bear the burden?

Then there are problems related to biases and preconceptions introduced into the AI directly by the developers, even if only unconsciously because they live in a certain part of the world and not in another, or because of their gender, or because of the images on which the models were then developed. If the image sets depict mostly white men in positions of power, the AI will reflect this condition when the query is 'government president giving a speech from a podium'. Discrimination related to gender, geographical origin or particular disabilities can be reflected in AI designs and sometimes amplified, as has happened in past experiments that ended badly.

Those who are less critical of these problems say that after all, through their behaviour, AIs reflect that of the societies that produced them, so they do not offer models that are worse than reality. And that if we want to change things in general, the improvement must first take place on this side of the screen so that they can then be reflected in a multidimensionality of mathematical spaces that will bring into existence a cute sloth in a woolly hat, intent on using a computer.